Bible

"The Holy Bible" redirects here. For the album, see The Holy Bible (album).

The Bible (from Greek τὰ βιβλία ta biblia "the books") is the collections of the primary religious texts of Judaism and Christianity. There is no common version of the Bible, as the individual books (Biblical canon), their contents and their order vary among denominations. Mainstream Judaism divides the Tanakh into 24 books, while a minority stream of Judaism, the Samaritans, accepts only five. The 24 texts of the Hebrew Bible are divided into 39 books in Christian Old Testaments, and complete Christian Bibles range from the 66 books of the Protestant canon to the 81 books in the Ethiopian Orthodox Bible,[1] to the 84 books of the Eastern Orthodox Bible.

The Jewish Bible, or Tanakh, is divided into three parts: (1) the five books of the Torah ("teaching" or "law"), comprising the origins of the Israelite nation, its laws and its covenant with the God of Israel; (2) the Nevi'im ("prophets"), containing the historic account of ancient Israel and Judah plus works of prophecy; and (3) the Ketuvim ("writings"): poetic and philosophical works such as the Psalms and the Book of Job.[2]

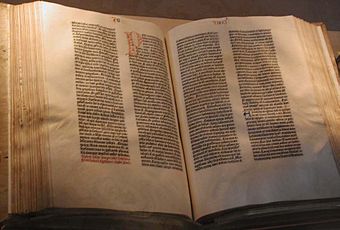

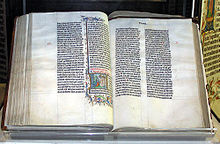

The Christian Bible is divided into two parts. The first is called the Old Testament, containing the (minimum) 39 books of Hebrew Scripture, and the second portion is called the New Testament, containing a set of 27 books. The first four books of the New Testament form the Canonical gospels which recount the life of Christ and are central to the Christian faith. Christian Bibles include the books of the Hebrew Bible, but arranged in a different order: Jewish Scripture ends with the people of Israel restored to Jerusalem and the temple, whereas the Christian arrangement ends with the book of the prophet Malachi. The oldest surviving Christian Bibles are Greek manuscripts from the 4th century; the oldest complete Jewish Bible is a Greek translation, also dating to the 4th century. The oldest complete manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible (the Masoretic text) date from the Middle Ages.[3]

During the three centuries following the establishment of Christianity in the 1st century, Church Fathers compiled Gospel accounts and letters of apostles into a Christian Bible which became known as the New Testament. The Old and New Testaments together are commonly referred to as "The Holy Bible" (τὰ βιβλία τὰ ἅγια). The canonical composition of the Old Testament is under dispute between Christian groups: Protestants hold only the books of the Hebrew Bible to be canonical; Roman Catholics and Eastern Orthodox additionally consider the deuterocanonical books, a group of Jewish books, to be canonical. The New Testament is composed of the Gospels ("good news"), the Acts of the Apostles, the Epistles (letters), and the Book of Revelation.

Contents |

Etymology

The English word Bible is from the Latin biblia, from the same word in Medieval Latin and Late Latin and ultimately from Greek τὰ βιβλία ta biblia "the books" (singular βιβλίον biblion).[4]

Middle Latin biblia is short for biblia sacra "holy book", while biblia in Greek and Late Latin is neuter plural (gen. bibliorum). It gradually came to be regarded as a feminine singular noun (biblia, gen. bibliae) in medieval Latin, and so the word was loaned as a singular into the vernaculars of Western Europe.[5] Latin biblia sacra "holy books" translates Greek τὰ βιβλία τὰ ἅγια ta biblia ta hagia, "the holy books".[6]

The word βιβλίον itself had the literal meaning of "paper" or "scroll" and came to be used as the ordinary word for "book". It is the diminutive of βύβλος bublos, "Egyptian papyrus", possibly so called from the name of the Phoenician port Byblos (also known as Gebal) from whence Egyptian papyrus was exported to Greece. The Greek ta biblia (lit. "little papyrus books")[7] was "an expression Hellenistic Jews used to describe their sacred books (the Septuagint).[8][9] Christian use of the term can be traced to ca. AD 223.[4]

Jewish canon

Development of the Jewish canon

Tanakh (Hebrew: תנ"ך) reflects the threefold division of the Hebrew Scriptures, Torah ("Teaching"), Nevi'im ("Prophets") and Ketuvim ("Writings"). The Hebrew Bible probably was canonized in three stages: 1) the Law - canonized after the Exile, 2) the Prophets - by the time of the Syrian persecution of the Jews, 3) and the Writings - shortly after 70 CE (the fall of Jerusalem).[citation needed] About that time, early Christian writings began to be accepted by Christians as "scripture". These events, taken together, may have caused the Jews to close their "canon".[citation needed] They listed their own recognized Scriptures, and excluded both Christian and Jewish writings considered by them to be "apocryphal". In this canon the thirty-nine books found in the Old Testament of today's Protestant Bibles were grouped together as twenty-two books, equaling the number of letters in the Hebrew alphabet. This canon of Jewish scripture is attested to by Philo, Josephus, and the Talmud.[7]

Torah

The Torah, or "Instruction", is also known as the "Five Books" of Moses, thus Chumash from Hebrew meaning "fivesome", and Pentateuch from Greek meaning "five scroll-cases". The Hebrew book titles come from some of the first words in the respective texts.

The Torah comprises the following five books:

- Genesis, Ge—Bereshith (בראשית)

- Exodus, Ex—Shemot (שמות)

- Leviticus, Le—Vayikra (ויקרא)

- Numbers, Nu—Bamidbar (במדבר)

- Deuteronomy, Dt—Devarim (דברים)

The Torah focuses on three moments in the changing relationship between God and the Jewish people. The first eleven chapters of Genesis provide accounts of the creation (or ordering) of the world and the history of God's early relationship with humanity. The remaining thirty-nine chapters of Genesis provide an account of God's covenant with the Hebrew patriarchs—Abraham, Isaac and Jacob (also called Israel)—and Jacob's children—the "Children of Israel"—especially Joseph. It tells of how God commanded Abraham to leave his family and home in the city of Ur, eventually to settle in the land of Canaan, and how the Children of Israel later moved to Egypt. The remaining four books of the Torah tell the story of Moses, who lived hundreds of years after the patriarchs. He leads the Children of Israel from their liberation from slavery in Ancient Egypt, to the renewal of their covenant with God at Mount Sinai and their wanderings in the desert until a new generation was ready to enter the land of Canaan. The Torah ends with the death of Moses.

The Torah contains the commandments of God, revealed at Mount Sinai (although there is some debate amongst Jewish scholars as to whether these were all written down at one time, or over a period of time during the 40 years of the wanderings in the desert). These commandments provide the basis for Halakha (Jewish religious law). Tradition states that there are 613 Mitzvot or 613 commandments. There is some dispute as to how to divide these up (mainly between the rabbis Ramban and Rambam).

The Torah is divided into fifty-four portions which in the Jewish liturgy are read on successive Sabbaths, from the beginning of Genesis to the end of Deuteronomy. The cycle ends and recommences at the end of Sukkot, which is called Simchat Torah.

Nevi'im

The Nevi'im, or "Prophets", tell the story of the rise of the Hebrew monarchy, its division into two kingdoms, and the prophets who, in God's name, warned the kings and the Children of Israel about the punishment of God. It ends with the conquest of the Kingdom of Israel by the Assyrians followed by the conquest of the Kingdom of Judah by the Babylonians and the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem. Portions of the prophetic books are read by Jews on the Sabbath (Shabbat). The Book of Jonah is read on Yom Kippur.

According to Jewish tradition, the Nevi'im are divided into eight books. Contemporary translations subdivide these into twenty-one books.

The Nevi'im comprise the following eight books:

- Joshua, Js—Yehoshua (יהושע)

- Judges, Jg—Shoftim (שופטים)

- Samuel, includes First and Second 1Sa–2Sa—Sh'muel (שמואל)

- Kings, includes First and Second, 1Ki–2Ki—Melakhim (מלכים)

- Isaiah, Is—Yeshayahu (ישעיהו)

- Jeremiah, Je—Yirmiyahu (ירמיהו)

- Ezekiel, Ez—Yekhezkel (יחזקאל)

- Twelve, includes all Minor Prophets—Tre Asar (תרי עשר)

- A. Hosea, Ho—Hoshea (הושע)

- B. Joel, Jl—Yoel (יואל)

- C. Amos, Am—Amos (עמוס)

- D. Obadiah, Ob—Ovadyah (עבדיה)

- E. Jonah, Jh—Yonah (יונה)

- F. Micah, Mi—Mikhah (מיכה)

- G. Nahum, Na—Nahum (נחום)

- H. Habakkuk, Hb—Havakuk (חבקוק)

- I. Zephaniah, Zp—Tsefanya (צפניה)

- J. Haggai, Hg—Khagay (חגי)

- K. Zechariah, Zc—Zekharyah (זכריה)

- L. Malachi, Ml—Malakhi (מלאכי)

Ketuvim

The Ketuvim, or "Writings" or "Scriptures," may have been written or compiled during or after the Babylonian Exile. Many of the psalms in the book of Psalms are attributed to David; King Solomon is believed to have written Song of Songs in his youth, Proverbs at the prime of his life, and Ecclesiastes at old age; and the prophet Jeremiah is thought to have written Lamentations. The Book of Ruth is the only biblical book that centers entirely on a non-Jew. The book of Ruth tells the story of a Moabitess who married a Jew and continued to follow the ways of the Jews after her husband's death; according to the Bible, she was the great-grandmother of King David. Five of the books, called "The Five Scrolls" (Megilot), are read on Jewish holidays: Song of Songs on Passover; the Book of Ruth on Shavuot; Lamentations on the Ninth of Av; Ecclesiastes on Sukkot; and the Book of Esther on Purim. Collectively, the Ketuvim contain lyrical poetry, philosophical reflections on life, and the stories of the prophets and other Jewish leaders during the Babylonian exile. It ends with the Persian decree allowing Jews to return to Jerusalem to rebuild the Temple.

The Ketuvim comprise the following eleven books, divided, in many modern translations, into twelve through the division of Ezra and Nehemiah:

- Psalms, Ps—Tehillim (תהלים)

- Proverbs, Pr—Mishlei (משלי)

- Job, Jb—Iyyov (איוב)

- Song of Songs, So—Shir ha-Shirim (שיר השירים)

- Ruth, Ru—Rut (רות)

- Lamentations, La—Eikhah (איכה), also called Kinot (קינות)

- Ecclesiastes, Ec—Kohelet (קהלת)

- Esther, Es—Ester (אסתר)

- Daniel, Dn—Daniel (דניאל)

- Ezra, Ea, includes Nehemiah, Ne—Ezra (עזרא), includes Nehemiah (נחמיה)

- Chronicles, includes First and Second, 1Ch–2Ch—Divrei ha-Yamim (דברי הימים), also called Divrei (דברי)

Hebrew Bible translations and editions

The Tanakh was mainly written in Biblical Hebrew, with some portions (notably in Daniel and Ezra) in Biblical Aramaic.[10]

The Oral Torah

According to some Jews during the Hellenistic period, such as the Sadducees, only a minimal oral tradition of interpreting the words of the Torah existed, which did not include extended biblical interpretation. According to the Pharisees, however, God revealed both a Written Torah and an Oral Torah to Moses, the Oral Torah consisting of both stories and legal traditions. In Rabbinic Judaism, the Oral Torah is essential for understanding the Written Torah literally (as it includes neither vowels nor punctuation) and exegetically. The Oral Torah has different facets, principally Halacha (laws), the Aggadah (stories), and the Kabbalah (esoteric knowledge). Major portions of the Oral Law have been committed to writing, notably the Mishnah; the Tosefta; Midrash, such as Midrash Rabbah, the Sifre, the Sifra, and the Mechilta; and both the Babylonian and Jerusalem Talmuds as well. It may have even influenced early Jewish Christianity.

Orthodox Judaism continues to accept the Oral Torah in its totality. Masorti and Conservative Judaism state that the Oral Tradition is to some degree divinely inspired, but disregard its legal elements in varying degrees. Reform Judaism also gives some credence to the Talmud containing the legal elements of the Oral Torah, but, as with the written Torah, asserts that both were inspired by, but not dictated by, God. Reconstructionist Judaism denies any connection of the Torah, Written or Oral, with God.

The article Jewish commentaries on the Bible discusses the Jewish understanding of the Bible, including Bible commentaries from the ancient Targums to classical Rabbinic literature, the midrash literature, the classical medieval commentators, and modern day Jewish Bible commentaries.

Septuagint

The Septuagint was a Greek translation of the Jewish scriptures. The Septuagint included books and additions not found in the Hebrew Bible. Modern Jewish Bibles follow the Masoretic Text rather than the Septuagint. The Septuagint splits certain books in two, so that the book of Kings, for example, became First Kings and Second Kings. Christian Bibles maintain these divisions. The Septuagint was adopted as the Christian Old Testament.

Christian canons

The Christian Bible consists of the Hebrew scriptures of Judaism, which are known as the Old Testament; and later writings recording the lives and teachings of Jesus and his followers, known as the New Testament. "Testament" is a translation of the Greek διαθηκη (diatheke), also often translated "covenant." It is a legal term denoting a formal and legally binding declaration of benefits to be given by one party to another (e.g., "last will and testament" in secular use). Here it does not connote mutuality; rather, it is a unilateral covenant offered by God to individuals.[7]

Groups within Christianity include differing books as part of one or both of these "Testaments" of their sacred writings—most prominent among which are the biblical apocrypha or deuterocanonical books.

Significant versions of the English Christian Bible include the Douay-Rheims, the RSV, the KJV, and the NIV. For a complete list, see List of English Bible translations.

In Judaism, the term Christian Bible is commonly used to identify only those books like the New Testament which have been added by Christians to the Masoretic Text, and excludes any reference to an Old Testament.[11]

Old Testament

The Old Testament consists of a collection of writings believed to have been composed at various times from the twelfth to the 2nd century BC. The books were written in classical Hebrew, except for brief portions (Ezra 4:8–6:18 and 7:12–26, Jeremiah 10:11, Daniel 2:4–7:28) which are in the Aramaic language, a sister language which became the lingua franca of the Semitic world.[12] Much of the material, including many genealogies, poems and narratives, is thought to have been handed down by word of mouth for many generations. Very few manuscripts are said to have survived the destruction of Jerusalem in AD 70.[12]

The Old Testament is accepted by Christians as scripture. Broadly speaking, it contains the same material as the Hebrew Bible. However, the order of the books is not entirely the same as that found in Hebrew manuscripts and in the ancient versions and varies from Judaism in interpretation and emphasis (see for example Isaiah 7:14). Christian denominations disagree about the incorporation of a small number of books into their canons of the Old Testament. A few groups consider particular translations to be divinely inspired, notably the Greek Septuagint, the Aramaic Peshitta, and the English King James Version.

Apocryphal or deuterocanonical books

The Septuagint (Greek translation, from Alexandria in Egypt under the Ptolemies) was generally abandoned in favour of the Masoretic text as the basis for translations of the Old Testament into Western languages from St. Jerome's Bible (the Vulgate) to the present day. In Eastern Christianity, translations based on the Septuagint still prevail. Some modern Western translations make use of the Septuagint to clarify passages in the Masoretic text, where the Septuagint may preserve a variant reading of the Hebrew text. They also sometimes adopt variants that appear in other texts e.g. those discovered among the Dead Sea Scrolls.

A number of books which are part of the Peshitta or Greek Septuagint but are not found in the Hebrew (Rabbinic) Bible are often referred to as deuterocanonical books by Roman Catholics referring to a later secondary (i.e. deutero) canon. Most Protestants term these books as apocrypha. Evangelicals and those of the Modern Protestant traditions do not accept the deuterocanonical books as canonical, although Protestant Bibles included them in Apocrypha sections until around the 1820s. However, the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches include these books as part of their Old Testament.

The Roman Catholic Church recognizes:

- Tobit

- Judith

- 1 Maccabees

- 2 Maccabees

- Wisdom

- Sirach (or Ecclesiasticus)

- Baruch

- The Letter of Jeremiah (Baruch Chapter 6)

- Greek Additions to Esther

- The Prayer of Azariah and Song of the Three Holy Children

- Susanna

- Bel and the Dragon

In addition to those, the Greek and Russian Orthodox Churches recognize the following:

Some other Eastern Orthodox Churches include:

- 2 Esdras i.e., Latin Esdras in the Russian and Georgian Bibles

There is also 4 Maccabees which is only accepted as canonical in the Georgian Church, but was included by St. Jerome in an appendix to the Vulgate, and is an appendix to the Greek Orthodox Bible, and it therefore sometimes included in collections of the Apocrypha.

The Anglican Churches uses some of the Apocryphal books liturgically. Therefore, editions of the Bible intended for use in the Anglican Church include the Deuterocanonical books accepted by the Catholic Church, plus 1 Esdras, 2 Esdras and the Prayer of Manasseh, which were in the Vulgate appendix.

Role in Christian theology

The Old Testament has always been central to the life of the Christian church. Bible scholar N.T. Wright says Jesus himself was profoundly shaped by the scriptures. He adds that the earliest Christians also searched those same scriptures in their effort to understand the earthly life of Jesus. They regarded the ancient Israelites' scriptures as having reached a climactic fulfillment in Jesus himself, generating the "new covenant" prophesied by Jeremiah.[13]

New Testament

The New Testament is a collection of 27 books, of 4 different genres of Christian literature (Gospels, one account of the Acts of the Apostles, Epistles and an Apocalypse). Jesus is its central figure. The New Testament presupposes the inspiration of the Old (2 Timothy 3:16). Nearly all Christians recognize the New Testament (as stated below) as canonical scripture. These books can be grouped into:

|

General Epistles, also called Jewish Epistles

Revelation, or the Apocalypse Re |

The order of these books varies according to Church tradition. The New Testament books are ordered differently in the Catholic/Protestant tradition, the Slavonic tradition, the Syriac tradition and the Ethiopian tradition.

Original language

The books of the New Testament were written in Koine Greek, the language of the earliest extant manuscripts, even though some authors often included translations from Hebrew and Aramaic texts.

Historic editions

When ancient scribes copied earlier books, they wrote notes on the margins of the page (marginal glosses) to correct their text—especially if a scribe accidentally omitted a word or line—and to comment about the text. When later scribes were copying the copy, they were sometimes uncertain if a note was intended to be included as part of the text. See textual criticism. Over time, different regions evolved different versions, each with its own assemblage of omissions and additions.

The autographs, the Greek manuscripts written by the original authors, have not survived. Scholars surmise the original Greek text from the versions that do survive. The three main textual traditions of the Greek New Testament are sometimes called the Alexandrian text-type (generally minimalist), the Byzantine text-type (generally maximalist), and the Western text-type (occasionally wild). Together they comprise most of the ancient manuscripts.

Development of Christian Canons

The Old Testament canon entered into Christian use in the Greek Septuagint translations and original books, and their differing lists of texts. In addition to the Septuagint, Christianity subsequently added various writings that would become the New Testament. Somewhat different lists of accepted works continued to develop in antiquity. In the 4th century a series of synods produced a list of texts equal to the 39, 46(51) ,54, or 57 book canon of the Old Testament and to the 27-book canon of the New Testament that would be subsequently used to today, most notably the Synod of Hippo in AD 393. Also c. 400, Jerome produced a definitive Latin edition of the Bible (see Vulgate), the canon of which, at the insistence of the Pope, was in accord with the earlier Synods. With the benefit of hindsight it can be said that this process effectively set the New Testament canon, although there are examples of other canonical lists in use after this time. A definitive list did not come from an Ecumenical Council until the Council of Trent (1545–63).[14]

During the Protestant Reformation, certain reformers proposed different canonical lists to those currently in use. Though not without debate, see Antilegomena, the list of New Testament books would come to remain the same; however, the Old Testament texts present in the Septuagint but not included in the Jewish canon fell out of favor. In time they would come to be removed from most Protestant canons. Hence, in a Catholic context, these texts are referred to as deuterocanonical books, whereas in a Protestant context they are referred to as the Apocrypha, the label applied to all texts excluded from the biblical canon but which were in the Septuagint. It should also be noted that Catholics and Protestants both describe certain other books, such as the Acts of Peter, as apocryphal.

Thus, the Protestant Old Testament of today has a 39-book canon—the number of books (though not the content) varies from the Tanakh because of a different method of division—while the Roman Catholic Church recognizes 46 books(51 books with some books combined into 46 books) as the canonical Old Testament. The Orthodox Churches recognise 3 Maccabees, 1 Esdras, Prayer of Manasseh and Psalm 151 in addition to the Catholic canon. Some include 2 Esdras. The Anglican Church also recognises a longer canon. The term "Hebrew Scriptures" is often used as being synonymous with the Protestant Old Testament, since the surviving scriptures in Hebrew include only those books, while Catholics and Orthodox include additional texts that have not survived in Hebrew. Both Catholics and Protestants have the same 27-book New Testament Canon.

The New Testament writers assumed the inspiration of the Old Testament, probably earliest stated in 2 Timothy 3:16, "all Scripture is inspired of God".[7]

Ethiopian Orthodox canon

The Canon of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church is wider than for most other Christian groups. The Ethiopian Old Testament Canon includes the books found in the Septuagint accepted by other Orthodox Christians, in addition to Enoch and Jubilees which are ancient Jewish books that only survived in Ge'ez but are quoted in the New Testament (citation required), also Greek Ezra First and the Apocalypse of Ezra, 3 books of Meqabyan, and Psalm 151 at the end of the Psalter. The three books of Meqabyan are not to be confused with the books of Maccabees. The order of the other books is somewhat different from other groups', as well. The Old Testament follows the Septuagint order for the Minor Prophets rather than the Jewish order.

Belief in divine inspiration

Some Christians adhere to a doctrine of biblical literalism, i.e. they regard both the New and Old Testament as the inerrant Word of God, spoken by God and written down in its perfect form by humans. Others hold the perspective of Biblical infallibility: that the Bible is free from error in spiritual but not scientific matters. "Bible scholars claim that discussions about the Bible must be put into its context within church history and then into the context of contemporary culture."[13]

Belief in sacred texts is attested to in Jewish antiquity,[15][16] and this belief can also be seen in the earliest of Christian writings. Various texts of the Bible mention Divine agency in relation to prophetic writings,[17] the most explicit being: "All scripture is breathed out by God and profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness."[2 Timothy 3:16]

In their book A General Introduction to the Bible, Norman Geisler and William Nix wrote: "The process of inspiration is a mystery of the providence of God, but the result of this process is a verbal, plenary, inerrant, and authoritative record."[18] Most evangelical biblical scholars[19][20][21] associate inspiration with only the original text; for example some American Protestants adhere to the 1978 Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy which asserted that inspiration applied only to the autographic text of Scripture.[22] A minority even within adherents of biblical literalism extend the claim of inerrancy to a particular translation, e.g. the King-James-Only Movement.

Bible versions and translations

Bible versions are discussed below, while Bible translations can be found on a separate page.

The original texts of the Tanakh were in Hebrew, although some portions were in Aramaic. In addition to the authoritative Masoretic Text, Jews still refer to the Septuagint, the translation of the Hebrew Bible into Greek, and the Targum Onkelos, an Aramaic version of the Bible. There are several different ancient versions of the Tanakh in Hebrew, mostly differing by spelling, and the traditional Jewish version is based on the version known as Aleppo Codex. Even in this version by itself, there are words which are traditionally read differently from written (sometimes one word is written and another is read), because the oral tradition is considered more fundamental than the written one, and presumably mistakes had been made in copying the text over the generations.

The primary biblical text for early Christians was the Septuagint or (LXX). In addition, they translated the Hebrew Bible into several other languages. Translations were made into Syriac, Coptic, Ge'ez and Latin, among other languages. The Latin translations were historically the most important for the Church in the West, while the Greek-speaking East continued to use the Septuagint translations of the Old Testament and had no need to translate the New Testament.

The earliest Latin translation was the Old Latin text, or Vetus Latina, which, from internal evidence, seems to have been made by several authors over a period of time. It was based on the Septuagint, and thus included books not in the Hebrew Bible.

Pope Damasus I assembled the first list of books of the Bible at the Council of Rome in AD 382. He commissioned Saint Jerome to produce a reliable and consistent text by translating the original Greek and Hebrew texts into Latin. This translation became known as the Latin Vulgate Bible and in 1546 at the Council of Trent was declared by the Church to be the only authentic and official Bible in the Latin Rite.

Especially since the Protestant Reformation, Bible translations for many languages have been made. The Bible has seen a notably large number of English language translations.

| Number | Statistic |

|---|---|

| 6,900 | Approximate number of languages spoken in the world today |

| 1,300 | Number of translations into new languages currently in progress |

| 1,185 | Number of languages with a translation of the New Testament |

| 451 | Number of languages with a translation of the Bible (Protestant Canon) |

The Bible continues to be translated to new languages, largely by Christian organisations such as Wycliffe Bible Translators, New Tribes Mission and the Bible society.

Biblical criticism

Biblical criticism refers to the investigation of the Bible as a text, and addresses questions such as authorship, dates of composition, and authorial intention. It is not the same as criticism of the Bible, which is an assertion against the Bible being a source of information or ethical guidance, or observations that the Bible may have translation errors.[24]

Higher criticism

In the 17th century Thomas Hobbes collected the current evidence to conclude outright that Moses could not have written the bulk of the Torah. Shortly afterwards the philosopher Baruch Spinoza published a unified critical analysis, arguing that the problematic passages were not isolated cases that could be explained away one by one, but pervasive throughout the five books, concluding that it was "clearer than the sun at noon that the Pentateuch was not written by Moses . . ." Despite determined opposition from Christians, both Catholic and Protestant, the views of Hobbes and Spinoza gained increasing acceptance amongst scholars.

Archaeological and historical research

Biblical archaeology is the archaeology that relates to, and sheds light upon, the Hebrew Scriptures and the New Testament. It is used to help determine the lifestyle and practices of people living in biblical times.

There are a wide range of interpretations of the existing Biblical archaeology. One broad division includes Biblical maximalism that generally take the view that most of the Old Testament or Hebrew Bible is essentially based on history although presented through the religious viewpoint of its time. It is considered the opposite of biblical minimalism which considers the Bible a purely post-exilic (5th century BC and later) composition. In any case, even accepting Biblical minimalism, the Bible is a historical document containing first-hand information on the Hellenistic and Roman eras, and there is universal scholarly consensus that the events of the Babylonian captivity of the 6th century onward have a basis in history.

On the other hand, the historicity of the biblical account of the history of ancient Israel and Judah of the 10th to 7th centuries BC is disputed in scholarship. The biblical account of the 8th to 7th centuries is widely, but not universally, accepted as historical, while the verdict on the earliest period of the United Monarchy (10th century BC) and the historicity of David is far from clear. For this reason, archaeological evidence providing information on this period, such as the Tel Dan Stele, can potentially be decisive.

Finally, the biblical account of events of the Exodus from Egypt in the Torah, and the migration to the Promised Land and the period of Judges are not considered historical in scholarship.[25][26]

Regarding the New Testament, the setting being the Roman Empire period in the 1st century, the historical context is well established. There has nevertheless been some debate on the historicity of Jesus, but the mainstream opinion is clearly that Jesus was one of several known historical itinerant preachers in 1st-century Roman Judea, teaching in the context of the religious upheavals and sectarianism of Second Temple Judaism.

See also

Biblical topics

- Alcohol in the Bible

- Circumcision in the Bible

- Crime and punishment in the Bible

- Ethics in the Bible

- Murder in the Bible

- Slavery in the Bible

- Women in the Bible

- Summary of Christian eschatological differences

Endnotes

- ^ "The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church". Ethiopianorthodox.org. http://www.ethiopianorthodox.org/english/canonical/books.html. Retrieved 2010-11-19.

- ^ Halpern, B. the First Historians: The Hebrew Bible. Harper & Row, 1988, quoted in Smith, Mark S.The early history of God: Yahweh and the other deities in ancient Israel. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.; 2nd ed., 2002. ISBN 978-0802839725, p.14

- ^ Philip R. Davies, "Memories of ancient Israel", p.7. Books.google.com.au. 2008-10-31. ISBN 9780664232887. http://books.google.com/?id=M1rS4Kce_PMC&lpg=PP1&dq=Memories%20of%20Ancient%20Israel&pg=PA7#v=onepage&q&f=false. Retrieved 2010-11-19.

- ^ a b Harper, Douglas. "bible". Online Etymology Dictionary. http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=bible.

- ^ "The Catholic Encyclopedia". Newadvent.org. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/02543a.htm. Retrieved 2010-04-23.

- ^ Biblion, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, at Perseus.

- ^ a b c d Stagg, Frank. New Testament Theology. Nashville: Broadman, 1962. ISBN 0-8054-1613-7.

- ^ "From Hebrew Bible to Christian Bible" by Mark Hamilton on PBS's site From Jesus to Christ: The First Christians.

- ^ Dictionary.com etymology of the word "Bible".

- ^ "Bible Study, Bible Facts". http://www.csbbc.net/bible.html. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ^ Accuracy of Torah Text.

- ^ a b Sir Godfrey Driver. "Introduction to the Old Testament of the New English Bible." Web: 30 November 2009

- ^ a b Wright, N.T. The Last Word: Scripture and the Authority of God—Getting Beyond the Bible Wars. HarperCollins, 2005. ISBN 0060872616 / 9780060872618

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia: Canon of the New Testament: "The idea of a complete and clear-cut canon of the New Testament existing from the beginning, that is from Apostolic times, has no foundation in history. The Canon of the New Testament, like that of the Old, is the result of a development, of a process at once stimulated by disputes with doubters, both within and without the Church, and retarded by certain obscurities and natural hesitations, and which did not reach its final term until the dogmatic definition of the Tridentine Council."

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, De vita Moysis 3.23.

- ^ Josephus, Contra Apion 1.8.

- ^ "Basis for belief of Inspiration Biblegateway". Biblegateway.com. http://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=2%20Sam%2023:2,2%20Tim%203:16,Luke%201:70,Heb%203:7,10:15-16,1%20Peter%201:11,Mark%2012:36,2%20Peter%201:20-21,Acts%201:16,Acts%203:18,Acts%2028:25;&version=50. Retrieved 2010-04-23.

- ^ Norman L. Geisler, William E. Nix. A General Introduction to the Bible. Moody Publishers, 1986, p.86. ISBN 0-8024-2916-5

- ^ For example, see Leroy Zuck, Roy B. Zuck. Basic Bible Interpretation. Chariot Victor Pub, 1991,p.68. ISBN 0-89693-819-0

- ^ Roy B. Zuck, Donald Campbell. Basic Bible Interpretation. Victor, 2002. ISBN 0-7814-3877-2

- ^ Norman L. Geisler. Inerrancy. Zondervan, 1980, p.294. ISBN 0-310-39281-0

- ^ International Council on Biblical Inerrancy (1978) (PDF). The Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy. International Council on Biblical Inerrancy. http://www.churchcouncil.org/ccpdfdocs/01_Biblical_Inerrancy_A&D.pdf.

- ^ Wycliffe Bible Translators, Inc. (WBT) Translation Statistics. July 2010: Wycliffe Bible Translators

- ^ EXPONDO OS ERROS DA SOCIEDADE BÍBLICA INTERNACIONAL

- ^ Finkelstein, Israel; Neil Silberman. The Bible Unearthed.

- ^ Dever, William. Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come from?.

References and further reading

| Find more about Bible on Wikipedia's sister projects: | |

| Definitions from Wiktionary |

|

| Images and media from Commons |

|

| Learning resources from Wikiversity |

|

| News stories from Wikinews |

|

| Quotations from Wikiquote |

|

| Source texts from Wikisource |

|

| Textbooks from Wikibooks |

|

| Wikiversity has learning materials about Biblical Studies (NT) |

- Anderson, Bernhard W. Understanding the Old Testament. ISBN 0-13-948399-3.

- Asimov, Isaac. Asimov's Guide to the Bible. New York, NY: Avenel Books, 1981. ISBN 0-517-34582-X.

- Berlin, Adele, Marc Zvi Brettler and Michael Fishbane. The Jewish Study Bible. Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-19-529751-2.

- Finkelstein, Israel; Silberman, Neil Asher (2001). The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-2338-1.

- Finkelstein, Israel; Silberman, Neil Asher (August 2002). "Review: "The Bible Unearthed": A Rejoinder". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 327: 63–73. JSTOR 1357859

- Herzog, Ze'ev (October 29, 1999). Deconstructing the walls of Jericho. Ha'aretz. http://mideastfacts.org/facts/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=32&Itemid=34

- Dever, William G. (March/April 2007). "Losing Faith: Who Did and Who Didn’t, How Scholarship Affects Scholars". Biblical Archaeology Review 33 (2): 54. http://creationontheweb.com/images/pdfs/other/5106losingfaith.pdf

- Dever, William G. Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come from? Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2003. ISBN 0-8028-0975-8.

- Ehrman, Bart D. Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why New York, NY: HarperSanFrancisco, 2005. ISBN 0-06-073817-0.

- Geisler, Norman (editor). Inerrancy. Sponsored by the International Council on Biblical Inerrancy. Zondervan Publishing House, 1980, ISBN 0-310-39281-0.

- Head, Tom. The Absolute Beginner's Guide to the Bible. Indianapolis, IN: Que Publishing, 2005. ISBN 0-7897-3419-2

- Hoffman, Joel M. In the Beginning. New York University Press, 2004. ISBN 0-8147-3690-4

- Lienhard, Joseph T. The Bible, The Church, and Authority. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1995.

- Lindsell, Harold. The Battle for the Bible. Zondervan Publishing House, 1978. ISBN 0-310-27681-0

- Masalha, Nur, The Bible and Zionism: Invented Traditions, Archaeology and Post-Colonialism in Palestine-Israel. London, Zed Books, 2007.

- McDonald, Lee M. and Sanders, James A., eds. The Canon Debate. Hendrickson Publishers (January 1, 2002). 662p. ISBN 1565635175 ISBN 978-1565635173

- Miller, John W. The Origins of the Bible: Rethinking Canon History Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 1994. ISBN 0-8091-3522-1.

- Riches, John. The Bible: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-19-285343-0

- Siku. The Manga Bible: From Genesis to Revelation. Galilee Trade (January 15, 2008). 224p. ISBN 0385524315 ISBN 978-0385524315

- Taylor, Hawley O. "Mathematics and Prophecy." Modern Science and Christian Faith. Wheaton: Van Kampen, 1948, pp. 175–83.

- Wycliffe Bible Encyclopedia, s.vv. "Book of Ezekiel," p. 580 and "prophecy," p. 1410. Chicago: Moody Bible Press, 1986.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||